Maybe everything in the world is perishable. Maybe the universe is perishable. Maybe everything is durations. And God, merely the longest of all. I don’t know.

What I do know is that the perishable differs a lot from the disposable. The perishable is a metaphysical condition which is surmountable through the acceptance of the hypothesis that the universe is finite. Disposability, on the other hand, is an economic-consumerist practice based on the illusion of infinitude.

I believe this is indeed a question that deserves the reflection of every artist because it concerns the nature, the spirit, and the appearance of their product.

Perishability is knowing we are going to die. Disposability is to commit suicide because of that.

Not to be or not to be, this is the question.

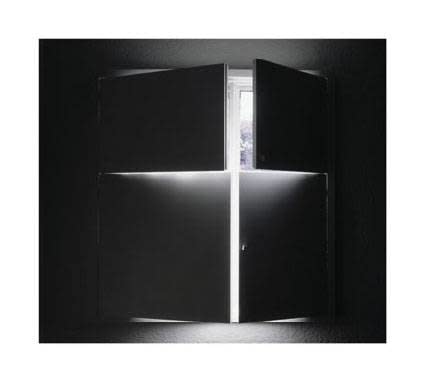

Cildo Meireles, about the work Obscura Luz

-

-

-

-

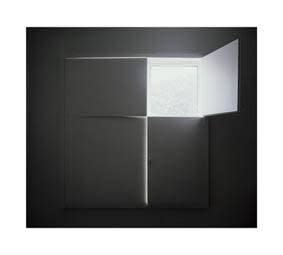

Luisa Lambri, Barragán House (2005)

The series of images were made at Casa Luis Barragán, the home of the modernist Mexican architect. Luisa Lambri captured a square window in the house, arranging the Dutch shutters in slightly different positions. The bright light that filters through produces cross-like configurations that have distinctly religious and Modernist overtones. Her large, mostly black-and-white images comment on the medium of photography and the legacy of Modernist abstraction through the work of other artists and architects.

-

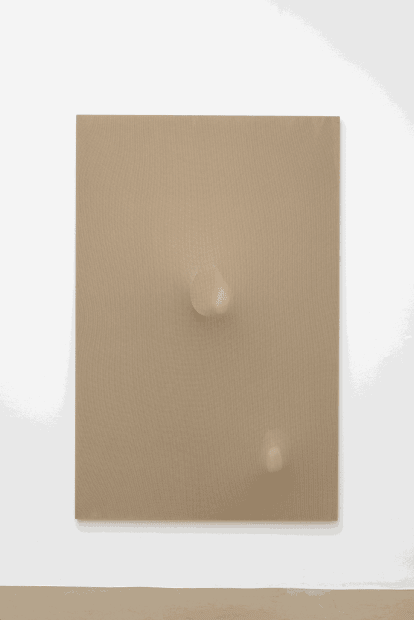

Anna Maria Maiolino, Sem título, da série Entre o Dentro e o Fora (2014)

'Maiolino’s exploring of paper and clay and their corporeity situates the work very close to Neo-Concrete practices, giving greater attention to the process of constructing than to what is constructed. Although her interest is similarly directed towards both the immediacy of the operation and the inevitable bodily connotation, she also tries to dissolve oppositions between subject and object, artist and spectator, nature and culture. Equally important as the exterior space is what Clark describes as “the feeling of a deep space inside ourselves”—the relation of a real outside space to an imaginary interior one. It is within the trivial tasks in every home that Maiolino finds a way to draw forth her moulded earthen work and to connect the subject with our primitive memory'.

'During the 1990s, as the banal evidence of the doing hand in daily life moulds the clay, the working process itself seems to bifurcate, taking Maiolino’s sculpture along two parallel paths. One leads to works that find their final shapes in the arrest of the casting procedure at the second phase in the execution of the mould. The work is the retrieved negative itself in The Shadow of the Other no. I series (1993), The Absentees (1993–1996), It’s What’s Missing series (1995–2001), and In & Out series (1995). As Maiolino describes, “The titles of these works refer to the existence of the opposite, the absent positive that has been separated from the negative. They form only one body at a given moment during the process of making the moulded sculpture. Thus, the process of those works incorporates the nostalgia for the matrix.” The mould, usually forgotten and discarded, she continues, “is endowed with new value by the emphasis given to its generative properties, to the vacant space, in which the memory of the other exists in its not being there: the positive-present in absence.”'

Catherine de Zegher (Maiolino’s Earthen Work or Enfooded Art)

-

-

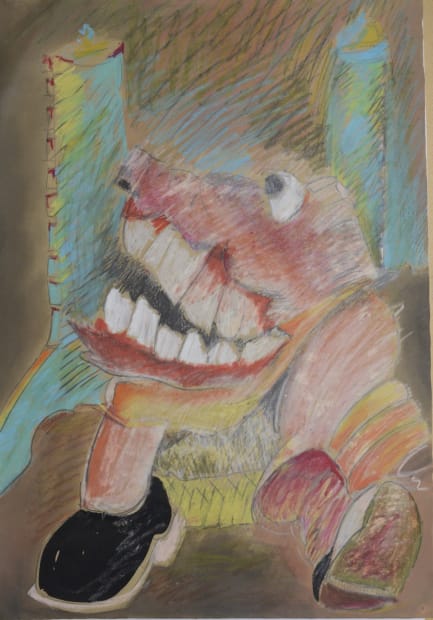

Clarissa Tossin, Vogais Portuguesas (2008)

On my first visit to Tossin’s studio, in early 2009, I encountered five resinous, amber-hued globules. Titled Portuguese Vowels (2008), the peculiar “organic” shapes, all of a size to hold in one’s hand, are not as amorphous as they first seem, but incredibly specific. Cast in sugar, the artist’s mouth served as mold, with the shape of the five molds determined by the pronunciation of each of the five major vowels, in Portuguese, mouth held in place as the mold set:2 A… E… I… O… U… I should have recognized the forms sooner: As a child, I had similar casts of my mouth made by my orthodontist, albeit in plaster rather than sugar. The choice in material is hardly arbitrary. Sugar, like the Portuguese language, represents a colonial history: Production of the crop structured the landscape, the economy, and the movement of bodies, as sugar became Brazil’s largest export good from the 16th century into the 18th century. The growing popularity of sugar in Europe fueled factory workers and the industrial revolution there as well as the increased importation of slaves from Africa into Brazil—a vicious cycle that ensured Portugal’s control over the colonial territory. There is some art historical material to account for here, too. See, for example, Nauman’s sculptures cast from body parts (e.g., the self-explanatory Wax Impressions of the Knees of Five Famous Artists, 1966), as well as his facial manipulations (Both Lips Turned Out / Mouth Open / Upper Lip Pushed…, a drawing from 1967) and his punning photograph Eating My Words (1966–67/1970). Hannah Wilke’s chewing gum sculptures (as in S.O.S.—Starification Object Series, 1975), similarly playful, and decidedly sexual, also come to mind. And before them there is Duchamp’s With My Tongue in My Cheek (1959), a plaster cast of the inside of the artist’s cheek mounted on a drawing of his profile. One can assume these references are also assumed—consumed— by the artist. Regardless, it’s amusing to imagine the process of casting candy vowels with the mouth, speaking of multitasking. How long did she hold each position—each note? What is the sound of a vowel cast in sugar? Did she drool while making them? Here, the body serves as a medium, a vehicle. The French noun véhicule is derived from the verb vehere, to carry, originating in the Latin vehiculum—carriage, conveyance. The body, mobilized, is a vehicle. The body conveys. It speaks; it sings. (And it occasionally drools: It exceeds; it loses control.) As a vehicle, it carries history, meaning—as an agent of consumption, an agent of translation (e.g., from sound to sculpture), an agent of transaction (from verb to noun).

(Text: Michael Ned Nolte, 2015)

-

![Gilson Plano Pássaro Verde, 2022 concreto, couro e encáustica [concrete, leather and encaustic] 40 x 32 x 5 cm](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/4cce1e85312551efbdd0029699da5dd1j/luisastrina-gilson-plano-p-ssaro-verde-2022.jpg)

![Bruno Baptistelli Sem título (série escura), 2022 tinta acrílica, carvão, linha e cabelo [acrylic paint, charcoal, thread and hair] 40 x 30 cm 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 in](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/494eebb076bae14c3f9f10fb4ec82ab0j/luisastrina-bruno-baptistelli-sem-t-tulo-s-rie-escura-2022.jpg)

![Janina McQuoid Coroa acesa, 2021 óleo sobre madeira [oil on wood] 33 x 24 cm [13 x 9 7/16]](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/c0672ff9f7cb4ec8ca2319b6892916c1j/luisastrina-janina-mcquoid-coroa-acesa-2021.jpg)

![Guilherme Ginane Fumaças, 2022 Óleo sobre madeira [Oil on wood] 39 x 19 cm [15 3/8 x 7 1/2 in]](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/549834c38b8ae8eedee3a931bfa5f3cej/luisastrina-guilherme-ginane-fuma-as-2022.jpg)

![Carole Gibbons Still Life, Vase and Cat, c. 2000 aquarela e pastel [watercolor and pastel] 41 x 29 cm / 16 1/8 x 11 3/8 in moldura [frame] 53 x 45 x 4 cm / 20 7/8 x 17 3/4 x 1 5/8 in](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/9f1eee97b667eef3a3511129c659295bj/luisastrina-carole-gibbons-still-life-vase-and-cat-c.-2000.jpg)

![Frederico Filippi Céu Fóssil III, 2017 spray, oil and acrílica sobre aço [spray, oil and acrylic on steel] 150 x 120 cm 59 1/8 x 47 1/4 in](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/b36f2dc56133d60b0a4d8be6ce98ba63p/luisastrina-frederico-filippi-c-u-f-ssil-iii-2017.png)

![Flávia Vieira Artefacts Showcase, 2022 tapeçaria e cerâmica [tapestry and ceramics] 80 x 50 cm 31 1/2 x 19 3/4 in](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/84ffa81eb0b6e9fdcffaf3cc4df673baj/luisastrina-fl-via-vieira-artefacts-showcase-2022.jpg)

![Flávia Vieira Performance. Rehearsal for Sphinx, 2022 cerâmica e aço [ceramics and steel] 130 x 75 x 45 cm 51 1/8 x 29 1/2 x 17 3/4 in](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/b0eaf160626bec60fc9d268338c3698aj/luisastrina-fl-via-vieira-performance.-rehearsal-for-sphinx-2022.jpg)

![Pedro Reyes Teocali, 2020 rocha vulcânica [volcanic stone] 50 x 15 x 15 cm 19 3/4 x 5 7/8 x 5 7/8 in](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/428c7dd7e422bf84d8849b819980be1cj/luisastrina-pedro-reyes-teocali-2020.jpg)

![Camila Sposati Tumbum-livre, 2015 cerâmica com base de metal [ceramic and metal base] 145 x 70 x 25 cm 57 1/8 x 27 1/2 x 9 7/8 in](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/1c865b2a041aed484fe82beec08c592dj/luisastrina-camila-sposati-tumbum-livre-2015.jpg)

![Gilson Plano Pássaro Branco, 2022 concreto, couro e encáustica [concrete, leather and encaustic] parte 1 - 44 x 31 x 8cm parte 2 - 53 x 22 x 5cm](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galerialuisastrina/images/view/3e8341f39c75058edca8956c4e2b5e39j/luisastrina-gilson-plano-p-ssaro-branco-2022.jpg)